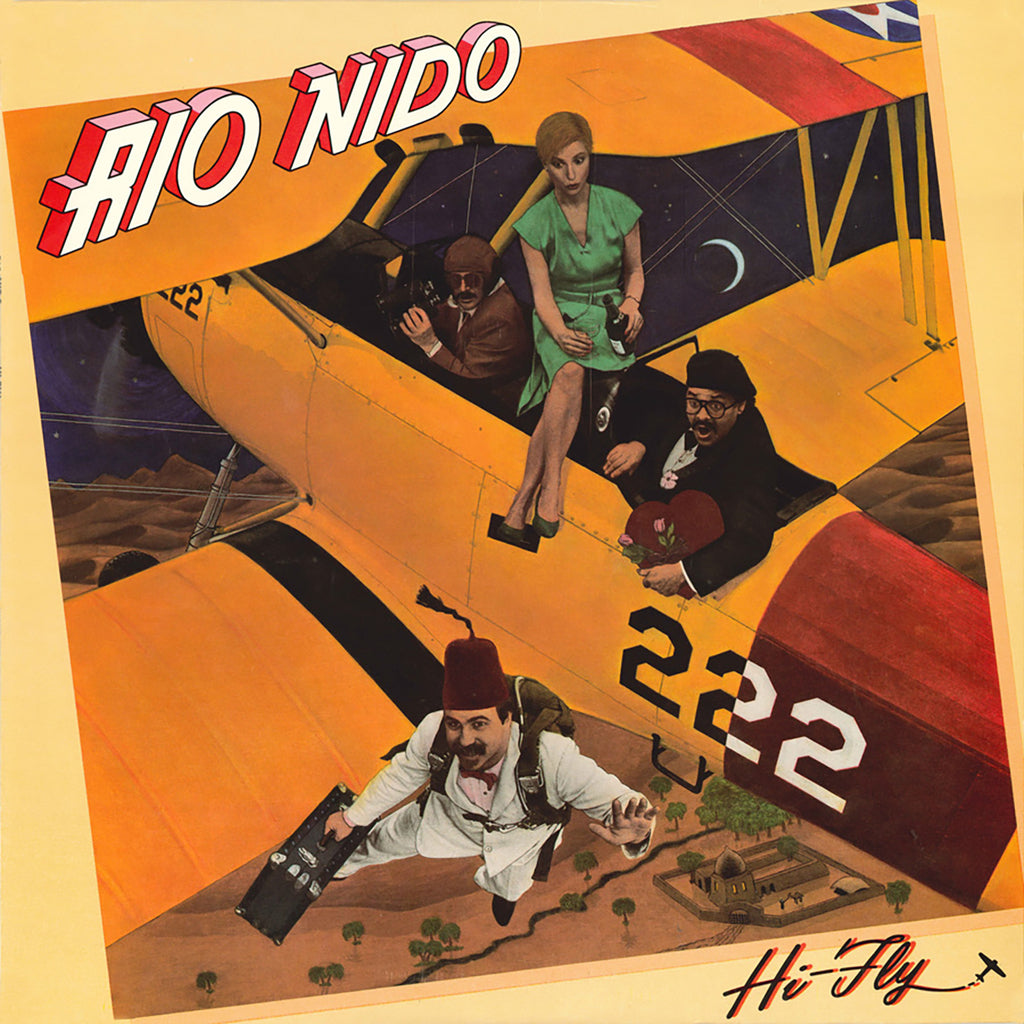

Available digitally for the first time! When Hi-Fly was released in 1987, it was clear that Rio Nido, a vocal group hailing from Minneapolis, had reached a new summit in its engagement with the jazz tradition. This wasn’t mere nostalgia, nor an academic exercise in vocalese transcription. It was something rarer: a genuine, swinging, fully alive conversation with the history of the music — the kind of conversation that honors its source without embalming it.

The trio at the time — Prudence Johnson, Roger Hernandez, and Tim Sparks — had internalized the lessons of Lambert, Hendricks & Ross, Eddie Jefferson, and even the Boswells, but filtered them through their own distinct musical dialect. They didn’t just sing the charts — they inhabited them, shaded them with surprise, and gave them pulse.

The album opens, fittingly, with Randy Weston’s “Hi-Fly”, a tune that has always invited flight, metaphorical and musical. The trio’s arrangement lifts off effortlessly — airy, assured, and rhythmically precise without ever sounding effortful. There’s a swing here that isn’t grafted on, but felt in the bones. It’s not just in the voices; it’s in the architecture of the phrasing, the subtle interplay with the rhythm section, and, crucially, in what’s left unsaid between the lines.

Prudence Johnson, a vocalist of extraordinary nuance and clarity, renders “You Don’t Know What Love Is” with emotional weight that never tips into sentimentality. Her performance on “That’s the Way to Treat Your Woman” (originally by Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson) is both knowing and wry, managing to wink at the lyric while never undermining it. Roger Hernandez brings a full, unforced baritone to the earthy “60 Minute Man”, giving it both grit and polish. And Tim Sparks, whose future solo work would reveal a deep fluency in both classical and world guitar idioms, demonstrates here the kind of musicianly instinct that doesn’t call attention to itself — except in its exquisite timing and harmonic savvy. His take on “A Night in Tunisia” is particularly nimble, both vocally and on the guitar.

The arrangements throughout reflect serious study, not just of harmony and counterpoint, but of feel. Their version of Bud Powell’s “Oblivion” — no easy vehicle — swings with authority, eschewing clinical precision for something more vital: groove. And on Slide Hampton’s “The Crawl”, they remind us that humor and swing are close relatives — their delivery is as tight as it is mischievous.

The instrumental support is never merely functional. Jimmy Hamilton, on piano, comps with taste and economy, and when he solos, the lines unfold with logic and ease. Dave Maslow’s bass playing is warm, grounded, and essential — not unlike Milt Hinton’s in spirit if not in tone. Dave Karr, a stalwart of the Midwest jazz scene, contributes saxophone parts that are both supportive and conversational. He’s the fourth voice, in a sense — lyrical, but never crowding the frame.

What distinguishes Hi-Fly isn’t just polish, though it’s certainly polished. It’s the sense that these musicians are part of a continuum. They understand the social and musical meaning of this material. The tradition is alive for them, not frozen. This is music made with deep respect — not reverence as distance, but reverence as participation.

In the years since its release, Hi-Fly has quietly gained the aura of a cult classic among vocal jazz aficionados. Its reissue in digital format by Compass Records is not just timely — it’s essential. The warmth of the Red House Records original remains intact, and the clarity of the production still feels fresh: no gimmicks, no gloss — just presence.

For those who still believe in the communal power of song, in the offhand eloquence of swing, and in the enduring alchemy of voices joined in harmony, Hi-Fly is not only worth hearing — it’s worth returning to. Often.